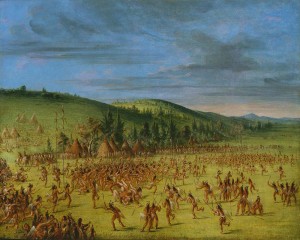

On Sunday April 20, 1806, Zebulon Pike was relaxing for a few days in the fort and settlement at Prairie du Chien — now in the state of Wisconsin, then in the newly organized Northwest Territories. In his journal he describes a lacrosse game:

This afternoon they had a great game of the cross on the prairie, between the Sioux on the one side, and the Puants and the Reynards on the other. The ball is made of some hard substance and covered with leather; the cross sticks are round, with net-work, and handles three feet long. The parties being ready, and bets agreed upon, (sometimes to the amount of some thousands of dollars,) the goals are erected on the prairie at the distance of half a mile; the ball is thrown up in the middle, and each party strives to drive it to the opposite goal; and when either party gains the first rubber, which is drawing it quite round the post, the ball is again taken to the centre, the ground changed, and the contest renewed ; and this is continued until one side gains four times, which decides the bet.

It is an interesting sight to behold two or three hundred naked savages contending on the plain, who shall bear off the palm of victory; as he who drives the ball round the goal receives the shouts of his companions, in congratulation of his success. It sometimes happens, that one catches the ball in his racket, and depending on his speed, endeavours to carry it to the goal; and when he finds himself too closely pursued, he hurls it with great force and dexterity to an amazing distance, where there are always flankers of both parties ready to receive it: it seldom touches the ground, but is sometimes kept in the air for hours before either party can gain the victory. In the game which I witnessed the Sioux were victorious, more, I believe, from the superiority of their skill in throwing the ball, than from their swiftness, for I thought the Puants and Reynards the fleetest runners.

I want to add some commentary, primarily for the purpose of clarification but also just some opinions about what this says about the human condition.

As to the two sides: the “Puants” are Ho Chunk (Winnebagoes). Puant is derived from the French word for “stink” and refers to the fact that they come from the shores of Lake Winnebago, which stunk. “Reynard” is French for Fox — the British and Americans usually called them the Fox. The actual name of the tribe is Meskwaki. The Sioux is a name given to a collection of several separate divisions, and likely the Sioux side in this contest were comprised of a combination of Yankton and Santee. The occasion of so many different peoples being in Prairie du Chien was an annual fur trading fair, where the native people gathered to trade their peltries and other goods (like maple syrup) which they had accumulated over the winter, in exchange for manufactured goods from the Northwest Fur Company — knives, cloth, guns, hatchets (tomahawks), traps, and of course liquor.

On the subject of alcohol, Pike himself lamented:

[M]ay not this be owing to their traders, who find it their interest to encourage their thirst after an article, which enables them to obtain their peltries at so low a rate as scarcely to be denominated a consideration, and have reduced the people near the establishment to a degree of degradation unparalleled?

Elsewhere in his account Pike makes it clear, however, that these trade fairs were fairly peaceful — in fact, he was surprised that this was true, given the alcohol consumption. So the reader should not jump to any stereotypical conclusions about the deleterious affects of alcohol, although obviously it often was a substantial social problem.

Pike was in the Prairie towards the end of an eight-month exploratory expedition to the Mississippi headwaters. In 1806 he was floating back downstream to St. Louis. At that time Lewis and Clark, whose expedition was another leg in the same national policy for gathering intelligence about and asserting authority in newly-acquired Louisiana, had not yet returned. As Pike went up the Mississippi, the Northwest Territories were on the east side, it is true, but the west side was Louisiana, and while the impetus for the trip was exploring Louisiana, in general federal authorities also knew very little about the far reaches of the older territory. Later within his same general mission — later in 1806, and continuing in 1807 — Pike took his more famous journey to Colorado and the American southwest, which then belonged to the Spanish.

The national and tribal groupings throughout the upper Mississippi valley were at various times engaged in warfare. The Sioux were in the midst of a low-level war with the Ojibwa (Chippewas) which had been carried on for generations. Elsewhere on his journey Pike negotiated truces between the Sioux and Ojibwa. Despite this background of warfare, somehow the contenders had clearly come to an agreement as to the rules of the contest. This measures the reduction in animosity, a testament to a level of organization and civilization that breaks down stereotypes about these “savages.” When a goal was scored, they willingly marched back to the center of the field, changed sides on it, and tossed the ball in the air to re-start play. They also knew when they were done (when one side scored four goals — a best of seven), so that the action was not mindlessly carried on as some type of pointless melee.

Pike was accurate and not prone to hyperbole in his journal, so when he said the goals were a half mile apart it is fair to assume that while he may not have measured it precisely, the field was still amazingly large! Of course with several hundred contestants, it would have to be, and no doubt the action switched between small clusters of participants giving the others a rest. He describes hurling the ball to “flankers” of players — this is like soccer, or even modern lacrosse, where the action concentrates within a few players while the rest more or less jog easily to position themselves. Overall, he gives a real sense of spectacle and it is fairly easy to imagine the scene in our minds eye.

There are many accounts about naked woodland Indians in surviving journals and other descriptions of this period. The baffling thing about this fact –that the various native peoples (especially, evidently, the men) were prone to activity in the nude — is not so much perceived propriety as the fact that for the most part it must have been cold! However, Pike records temperatures as one of his duties and on April 20, 1806, the high temperature reached 95 degrees under sunny skies — perhaps this mini heat wave was what prompted the decision to hold the match in the first place?

The most delightful part of Pike’s account is what we would call “post-game analysis.” This speaks to some type of timeless human condition, the need to express our opinions on sporting matches as well as other life events. It is easy to conjure up a vision of Pike and his fellow soldiers strolling back to the fort after the match, chattering away about what they just witnessed.

Some readers may doubt the claim that thousands of dollars were being wagered on the outcome of the game, but the trade at the fair involved high values. Beaver skins were used as a form of money, worth about $2 each. Games of chance and other gambling was not uncommon among the native peoples in general in the period.

Pike’s journal is available as a primary source on line. The account of the lacrosse game is only a small part of a wealth of detail in this journal which gives insight into these cultures during this period. It is delightful to read and seems to be well-balanced. If you are interested in getting an accurate picture of these lives in this time which looks beyond the stereotypes of popular media, this journal is a good place to start.