In and near the City of Tomahawk in northern Wisconsin, one of the earliest land purchases (land patent) was for a 110 acre parcel on the north side of Road Lake, a lakeside home neighborhood located just outside the southeast corner of the city limits. The purchaser was Hugh McIndoe as an assignee of a land grant issued to the University of Kentucky by the Morrill Act of 1862. The transaction occurred at the Stevens Point federal land office on March 1, 1870.

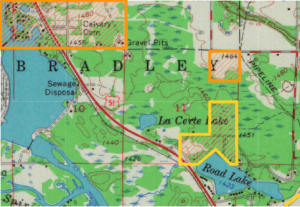

The outlined yellow area is the Kentucky land grant. Also shown are part of the present-day city limits, and Gilbert Vallier's homestead. The yellow line in the lower right corner is the Wausau-Ontonagon road.

It was under the Morrill Act that “land grant colleges” were founded, including familiar large public universities like Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota, California, Texas A&M and Purdue (the list goes on), as well as two notable private schools, Cornell and MIT. The Morrill Act was a means of providing financial support for education in the fields of agricultural and mechanical arts, practical academic fields which Congress felt needed to be strengthened in order to fuel economic growth. The most valuable asset of the federal government in the nineteenth century was its public lands. The lands were a source of income: direct federal land sales accounted for nearly 50% of all government revenues in the 1830s. And when the nineteenth century equivalent of federal subsidies were called for, rather than sell land and give the money to the states, acts such as the Morrill Act distributed the land itself to the states. The states and the universities thus endowed were allowed to sell these grants to private buyers, and that is what they usually did, using the cash to develop the schools.

At the time the lands were granted, many states in the east (in the 1860s Wisconsin was considered “the West”) had no more available federal lands, and so the land grant colleges were endowed with rights to lands in states that still had substantial open public regions such as Wisconsin and Minnesota. An extremely active land-grant assignee in the 1860s in the state of Wisconsin was Ezra Cornell, the namesake of the Ivy League school. Cornell was a friend of Samuel Morse of telegraph fame, and founded Western Union. Quoting from the Cornell University Press web site:

A provision of the Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862 allowed Cornell University to acquire 500,000 acres of valuable timberland in northern Wisconsin. Although most land grant universities immediately sold the federal tracts that had been allocated to them, Cornell held the land to allow it to appreciate. While the university was guarding its rights as a trustee of this estate, dealing with the supervisors and tax collectors of several counties, and negotiating with lumbermen, it did not escape criticism for its role as an absentee landlord. As Paul Wallace Gates details in The Wisconsin Pine Lands of Cornell University, the university’s perseverance paid off—the eventual sale of surface rights to the land yielded a five-million-dollar endowment and is regarded as one of the most successful episodes of land speculation in U.S. history.

The state of Kentucky followed the more typical strategy and cashed in its rights as soon as practical, rather than try to manage its land portfolio directly the way Cornell did. Other acquisitions near Tomahawk included grants to the University of Maryland and the University of Illinois. UI at the time was known as Illinois Industrial University, which is the name listed on the patents along with the first university president, John Milton Gregory. Some of the UI grants are along Bearskin Creek. Nazare Fauafau brokered a deal for 320 acres in the upper reaches of Little Somo River behalf of Maryland.

The assignee in the Road Lake purchase was Hugh McIndoe, a native of Scotland and brother of the early Wisconsin politician Walter McIndoe. The McIndoes were land speculators and lumbermen with sawmill operations in Wausau, and were major figures in the 1850s in that city. Walter was seven years older and a significantly more public figure, serving several terms in Congress at the time of the Civil War.

Most of the Morrill Act grants were assigned to brokers or purchased by timber interests, and while there was a lot of personal wealth gained by the likes of the McIndoes, as well as pure investment firms such as the Preston, Kean banking house of Chicago, these assignments were entirely above board. They were a means of liquidating the grants so the colleges could endow themselves via cash, and diversify the grants in the form of other investments.

While the system was not corrupt in a narrow sense, broadly speaking it was often the brokers who realized the greatest accumulation of wealth in the process. There were thousands of these transactions, and the land broker only needed to make a small profit on each one to garner vast wealth. The brokers had the unique knowledge needed to assess these grants, and therefore virtually held a monopoly on the credibility needed to conduct land transactions. Many if not most of these land patents were also ultimately turned into standalone investment instruments equally liquid with stock, bond and commercial paper markets. Investors could send telegrams to a banking house and buy and sell rights to these lands on virtually an instantaneous basis.

Almost none of the Morrill Act grants were used by settlers, although sometimes the landholder rented the property to tenant farmers, and the politics of absentee landlord-ism and settler rights heavily colored the political climate in the state. (An exception: It is likely that Nazare Faufau was not a pure speculator. He was a large individual landowner but made a living by combining knowledgeable acquisition of land with actual logging operations on that land as an owner -operator.)

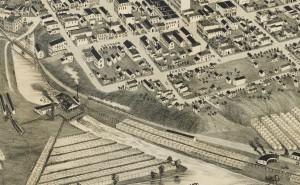

By 1881, both McIndoe brothers had died (relatively young, ages 49 and 52), but their sawmill was still in operation in the vicinity of this scene.

An important factor in McIndoe’s decision to select this piece of property no doubt was based on the proximity to the Wausau-Ontonagon Road. By 1870 the road (officially the Wausau and North State Line Road) was a well-traveled wagon road, supplying logging camps in the Tomahawk River and Upper Wisconsin River basins. It also was an important overland mail, cattle and supply artery to the copper mines along Lake Superior. Originally built in the mid 1850s, and improved in several stages throughout the 1860s and 1870s, this road generally followed the Wisconsin River from Wausau to Pelican Station (Rhinelander), but in the vicinity of the Ojibwe village called Skanawan (the village was located just north of where present-day highway 107 crosses Skanawan Creek) it veered northeast in a shortcut to the river at a point now inundated by Lake Alice. The McIndoe/Kentucky land purchase was less than a mile from the Wausau-Ontonagon road, and surely McIndoe or one of his employees selected the tract carefully for its overall value based on its proximity to this road as well as other factors like the percentage of swamp land and the density of the timber.

Between 1865 and 1869, 1.1 million acres of federal land in Wisconsin was acquired by college land grant entities throughout the state. The importance of the relationship between the valuation of this land and the ultimate endowment of these schools, as well as the effect on commercial development in the timberland of northern Wisconsin, seems to be vastly underestimated in the general public consciousness. These local connections, while perhaps mostly of interest to the Tomahawk community, hopefully provide general insight into this this important aspect of northwoods of history.